- October 30, 2025

Chasing a Ghost : PXA Stealer Part 2

A follow-up to a previous article on LoneNone and his PXA Stealer malware where we detail some rare insights into the malware author's back-end operations and the evolution of their capabilities.

Executive Summary

In August, Beazley Security Labs and SentinelOne Labs published collaborative research a python infostealer caught with a novel delivery method. Our team originally begun our investigation after our MDR team identified and contained the activity in a Beazley Security client environment. In part one of of this series, we focused primarily on analysis detailed the deception-ridden infection chain and capabilities of the final Python based infostealer payload, dubbed PXA Stealer.

In part two, we’ll detail how operational missteps from the threat actor revealed uncommon insights into infrastructure, operations, and the development of capabilities by the threat actor that are not usually seen by responders and cyber security researchers.

Do you want to see screenshots from a threat actor’s computer as they develop an infostealer and delivery campaign? Then read on.

Background and Context

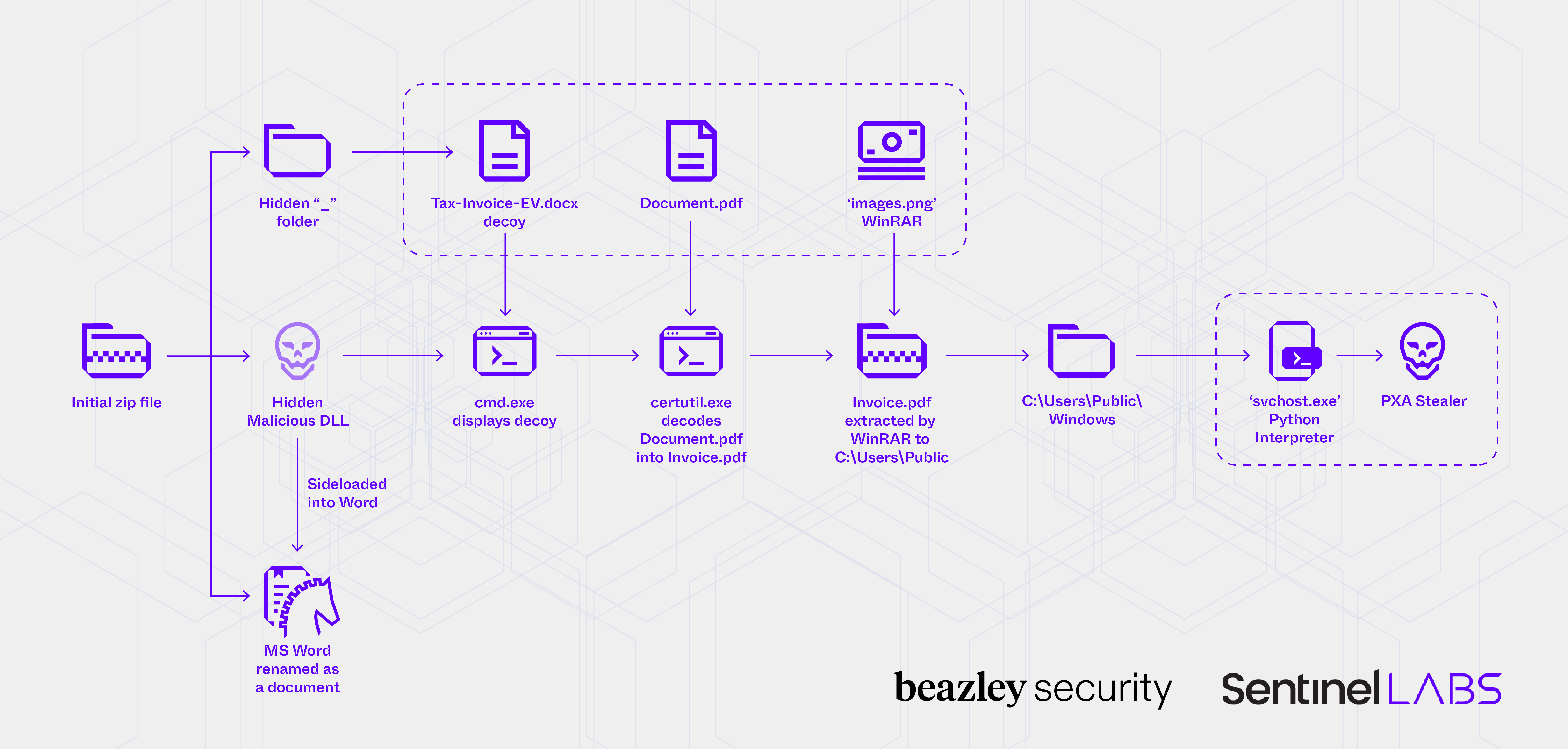

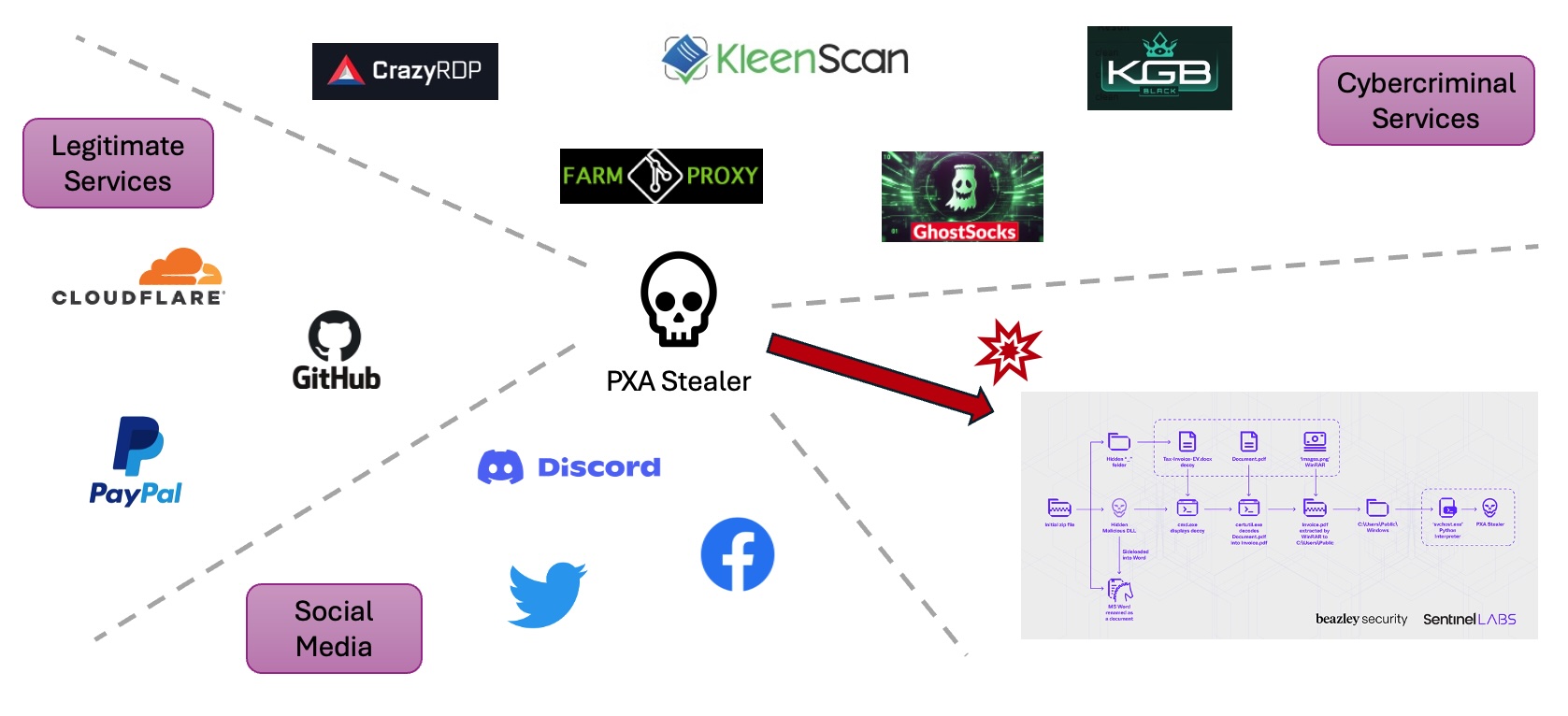

In August, Beazley Security’s MDR team responded to and contained an attempted infostealer infection campaign in a client environment, which we later identified as PXA Stealer. In collaboration with colleagues from SentinelOne Labs, our analysis of the infection chain revealed several notable deception techniques targeting not only the intended victim but also responding SOC analysts. As a quick refresher, below is the attack chain diagram from that analysis:

Figure 1: PXA Stealer infection chain

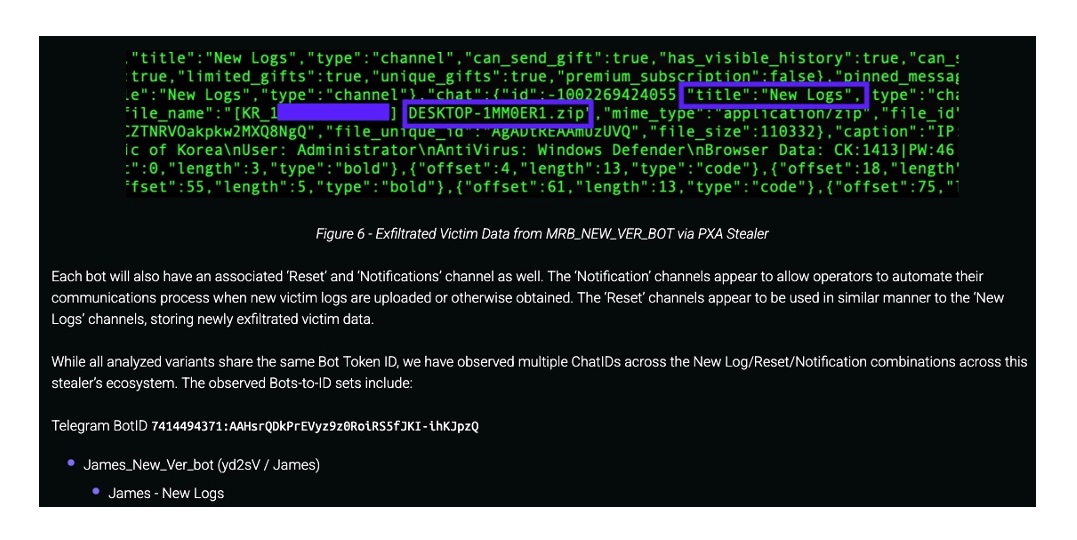

Modern day malware operations like the one described have become fully-fledged criminal enterprises complete with software development lifecycles, cloud infrastructure, and even customer service components, and it is common to gain a little visibility into these elements when responding to incidents. For example, when analyzing the Python components of PXA Stealer, we were able to identify the telegram channels where stolen data was being warehoused for eventual sale:

Figure 2: Original analysis and discovery of Telegram infrastructure

However, during this initial analysis, we discovered something uncommon that gave us a whole new level of insight.

QA Testing or Operational Misstep?

As mentioned in the previous article, we started with two big clues as starting points for threat intelligence analysis:

The threat actor referenced their handle “LoneNone” in various places in their infrastructure (most notably in the subdomain of the Cloudflare worker), and

We were able to identify some of the Telegram channels “LoneNone” was using in their operations

When we started digging into the Telegram infrastructure, a colleague from SentinelOne quickly noticed a very enticing set of credential packages. As often happens in these team research chats, there is sometimes an “ah ha!” moment that leads to breakthroughs, and this was certainly one of them:

Figure 3: ‘Ah ha!’

It turns out that LoneNone had run PXA Stealer on one of their own machines, and the malware dutifully packaged up whatever credentials, screenshots, and other data it could hoover up and uploaded them right into the same Telegram channel our teams happened to be monitoring.

Now, to be clear, we don’t know if this was the threat actor testing the malware for verification, or if this was an actual mistake, but we were not about to look a gift horse in the mouth. We wanted to see what we got …

The “loot”

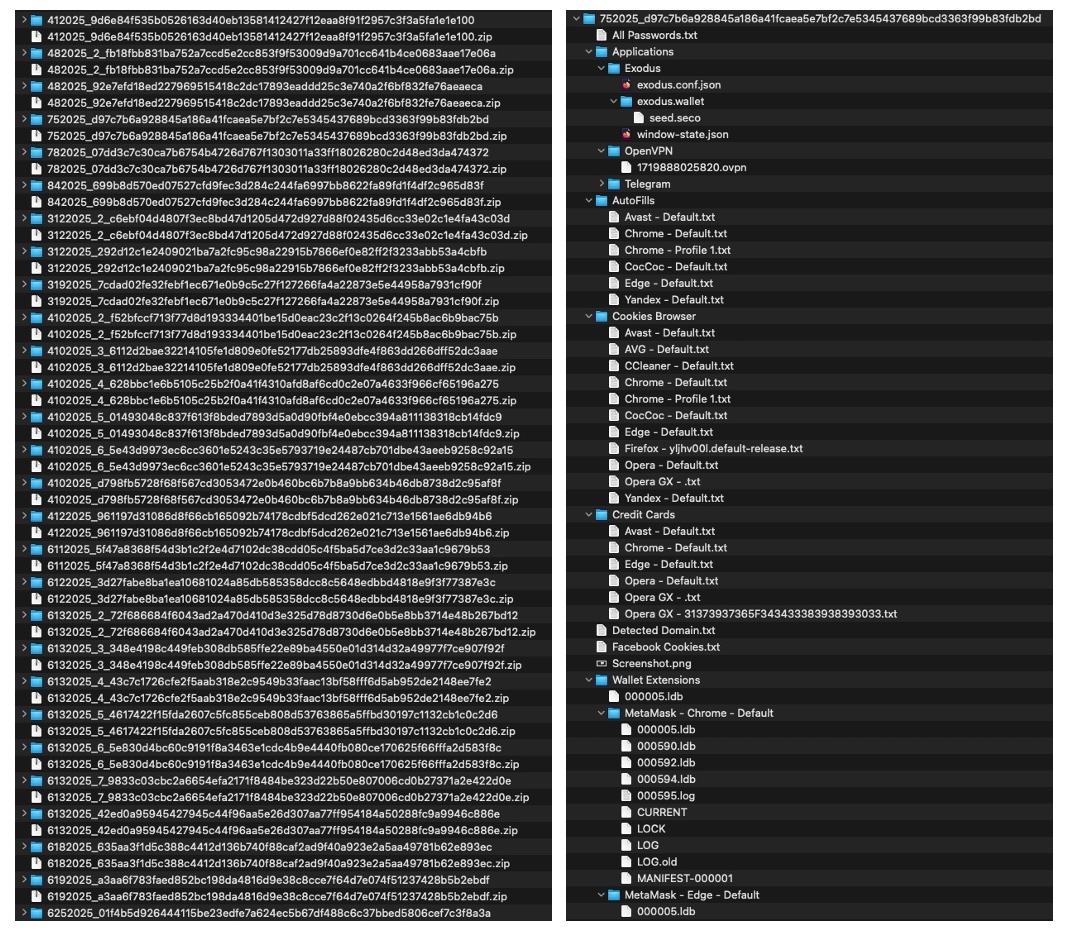

… and it was a lot. Turns out PXA Stealer ran on LoneNone’s own computers around 30 times, and each execution created a “package” for upload to telegram.

As mentioned before, cybercrime is an industry, and malware authors are now in competition with each other to create better, faster, stealthier, more feature rich malware to boost their sales. Infostealers accordingly have evolved to steal not only passwords, but data from browser autofill, crypto wallets, VPN software, file transfer applications, API tokens, anything not virtually bolted down. So, we suddenly had access to all that data from one (some?) of LoneNone’s operational computers:

Figure 4: All the packages on the left, and partial contents of one package on the right

We don’t often get a chance to study a cybercriminal operation quite this closely and with this much data to sift through, so we rolled up our sleeves and started organizing and making sense of what type of data we had access to. As part of our analysis, we were able to organize the various accounts into two general categories:

Infrastructure used to facilitate attacks

These are accounts for systems and services used to carry out attack campaigns. Some are legitimate services, while some exclusively cybercriminal services such as:

Social media accounts used to advertise and/or push malware

Legitimate service accounts to host malware components

Cybercriminal services used to facilitate attacks (like bullet proof hosting providers, binary crypters, and network traffic proxies)

Figure 5: Attack Infrastructure

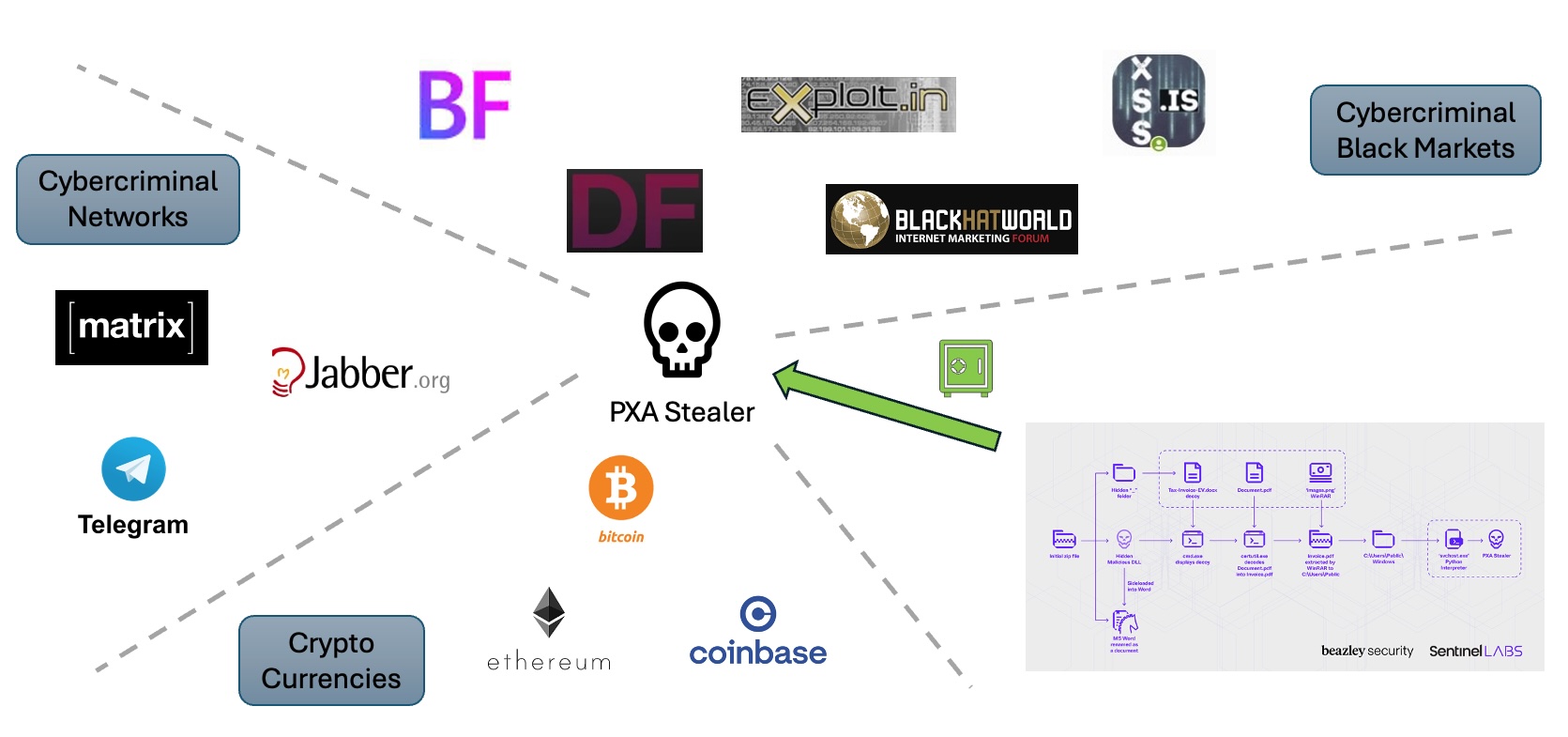

Accounts to sell data stolen by the PXA infostealer

These accounts are mostly used to warehouse stolen data and help facilitate the sale of it to other cybercriminals. This included:

Crypto currency wallet data

Communication apps like Telegram and Jabber

Accounts to well-known cybercriminal forums and marketplaces

Figure 6: Black Markets

To be clear, some of the services pictured above were not part of the data set, they have been included to comprehensively illustrate each category. Additionally, many of the accounts we gained visibility into no longer worked or led to dead ends. This lends credence to the theory that the computer(s) LoneNone ran PXA Stealer on were likely operational or development boxes, and potentially not personal computers.

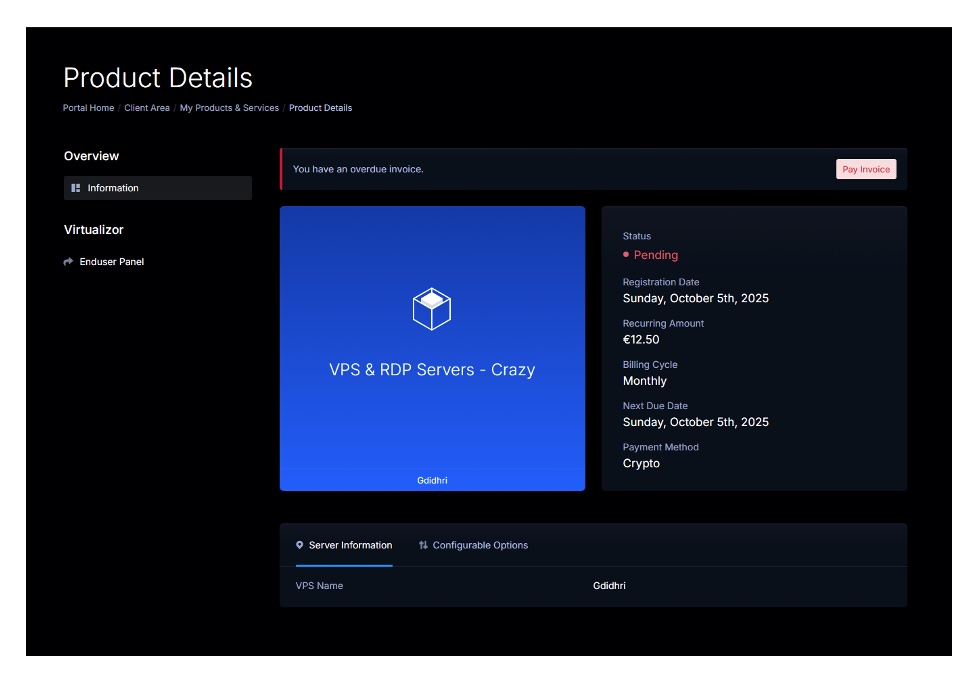

For an example account, we quickly honed on an XSS[.]is forum account. XSS is a well-known, gated cybercrime community where a significant number of well-known cyber-criminal groups do “business”. Alas, that specific account had already been de-activated. We also ran into similar walls on some operational accounts, such as LoneNone’s CrazyRDP account, where a VPS had been deactivated because of a past-due invoice:

Figure 7: Past-due bills

There were some accounts, however, that generated great investigative leads.

The Evolution of a Cyber Criminal Operation

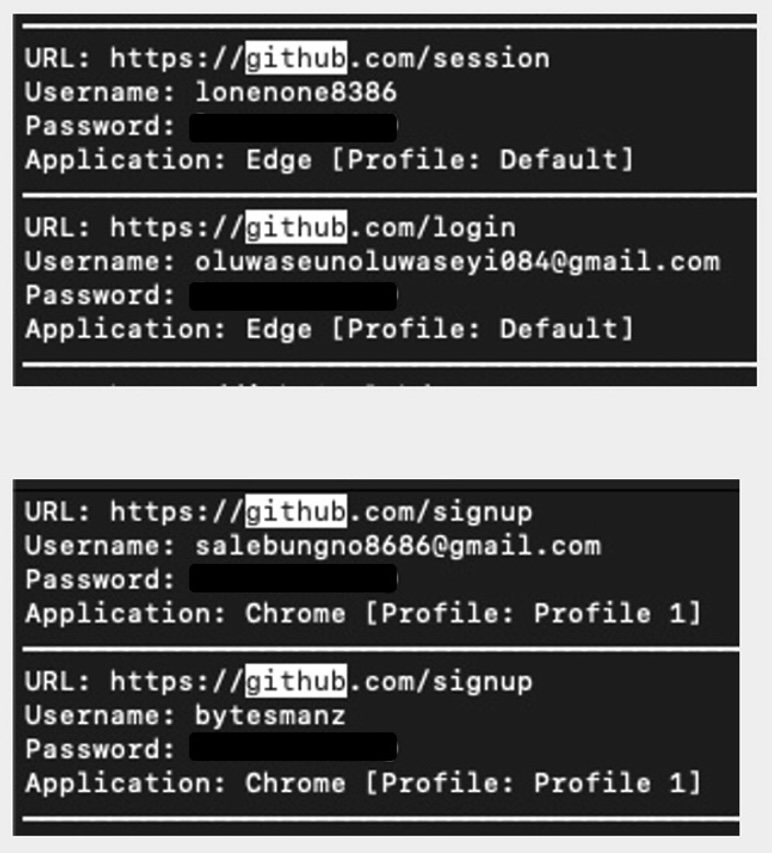

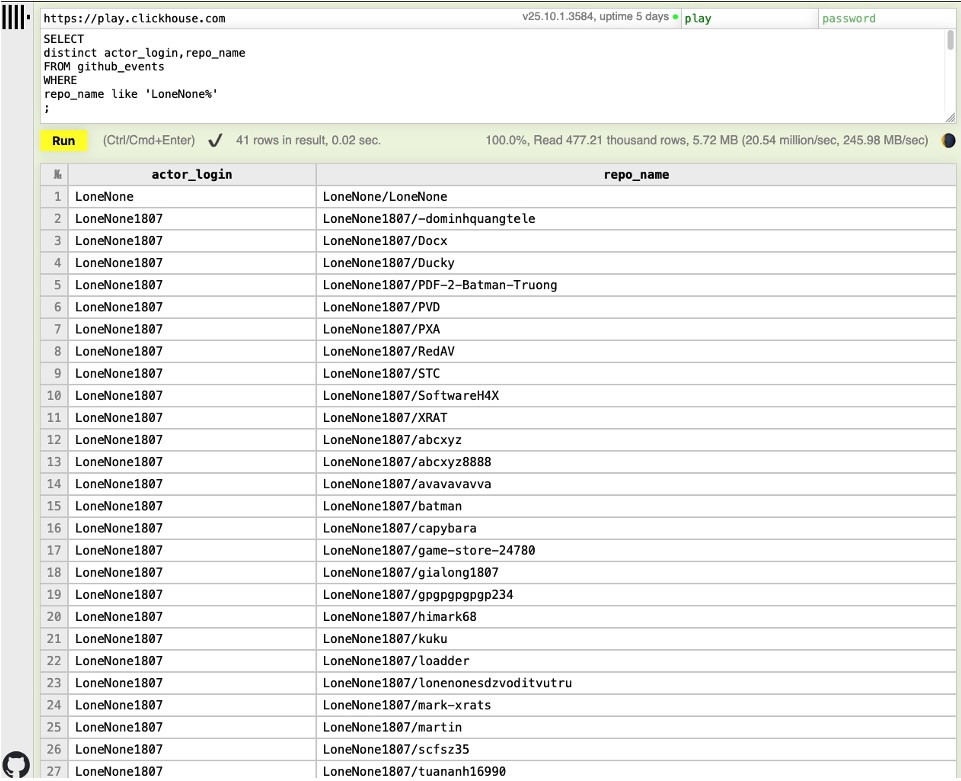

In the dataset, we discovered four different GitHub accounts that used the same password scheme:

Figure 8: GitHub Accounts

Unfortunately, we once again ran into four deactivated accounts. However, for GitHub specifically, there is a workaround! ClickHouse is an organization that created an open-source DBMS / “big data” system, and as a demonstration of their capability, they maintain a publicly searchable real-time index of all GitHub public actions. A very interesting side effect of that fantastic project is that we have a very powerful CTI research tool that enables us to identify historical (and now deactivated) GitHub repositories. As part of our research, we aimed that tool at LoneNone’s GitHub and found the following:

Figure 9: Since-deleted LoneNone GitHub repositories

Combine the above results with the WaybackMachine and we can take a peek at some of this defunct infrastructure hosted on GitHub. As we started to investigate these repos, we found some prior research into these Github repos that was published. Last year, Xavier Mertens wrote an article for Sans with some excellent reverse engineering work on components referencing the “RedAV” and “martin” repositories shown in the screenshot above. That excellent article absolutely deserves a read and can be found here.

Xavier showed that the sample he studied will:

- 1.

retrieve a Python310 environment package from the “RedAV” repo

- 2.

retrieve encoded objects from the “martin” repository

- 3.

decode those objects into Python scripts that reference the name ‘REDAV’

- 4.

eventually download and install third-party commodity malware XWorm (a known Remote Access Trojan) and Redline (an infostealer)

To be clear: LoneNone was not using GitHub to store project source code for the purposes of change control and version tracking. They were however abusing GitHub to stage and transmit encoded components of a malware infection chain.

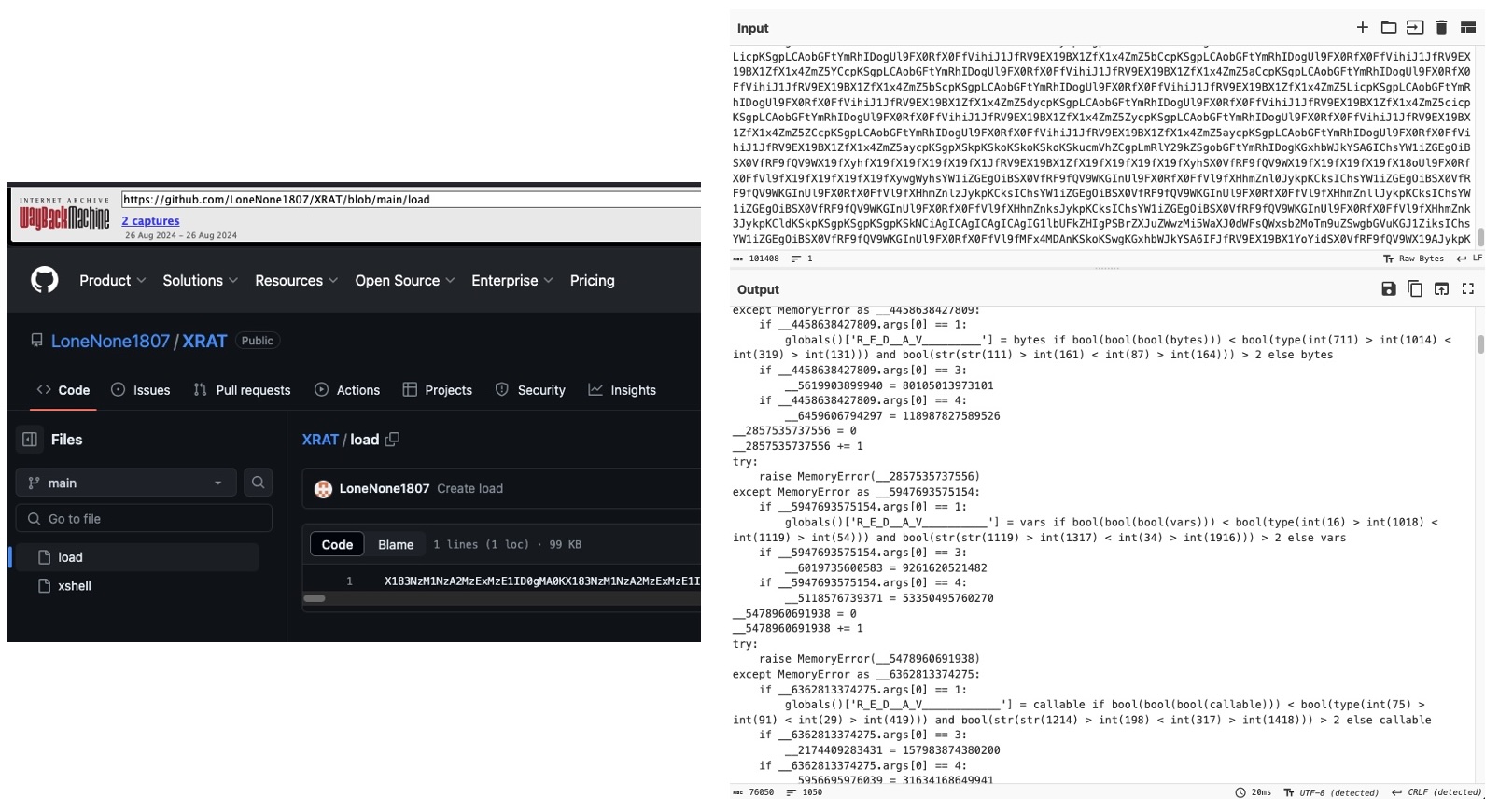

Armed with this knowledge, we looked through the other repositories and confirmed similar contents (outlined by the repo pictured below):

Figure 10: XRAT repo on the right, decoded ‘load’ component on the left

XRAT: RedAV + XWorm + Redline

SoftwareH4X: RedAV + XWorm + Redline

gialong1807: RedAV + XWorm + Redline

himark68: RedAV + XWorm + Redline

mark-xrats: RedAV + XWorm + Redline

Additionally, our analysis of the “RedAV” repository revealed references to the ‘avavavavva’ repository, which had Python code snippets similar to the above, but instead had the name ‘REDDEFENDER’, possibly showing different malware names LoneNone was experimenting with.

Taking a step back from this tangled web of encoded GitHub objects that call and reference each other, we paused to take a “thousand-foot view” and noticed the following timeline:

August 2024 – Xavier Mertens publishes analysis on LoneNone’s RedAV+XWorm+Redline campaign

August 2024 – WaybackMachine’s archives last snapshot of all LoneNone’s GitHub repos

November 2024 – Cisco Talos published first report of PXA Stealer

So, we believe we are looking at the evolution of LoneNone’s cybercriminal operations. In 2024, they were using GitHub to stage and deliver RedAV, XWorm, and Redline. Now, in 2025, they have completed and deployed their very own PXA Stealer using the much more robust paste[.]rs and 0x0[.]st (detailed in our previous blog) for staging and delivery.

This makes good business sense, as XWorm and Redline are both commodity malware, so budgeting for them would affect profits:

Malware Campaign Component | 2024: Old and Busted | 2025: New Hotness |

|---|---|---|

Malware Object Staging and Delivery | GitHub – well known, historically indexed and searchable, possibly susceptible to takedown requests | paste[.]rs and 0x0[.]st – anonymous and ephemeral “pastebin style” sites, much less friendly to historical searching by pesky cyber researchers |

RAT | XWorm – Third party, requires budget, eats into profit | N/A – saves money! |

InfoStealer | Redline – Third party, requires budget, forced to trust their infrastructure, eats into profit | PXA Stealer – malware now in-house, saves money! |

Copyright Infringement Lures: Work With What You Know

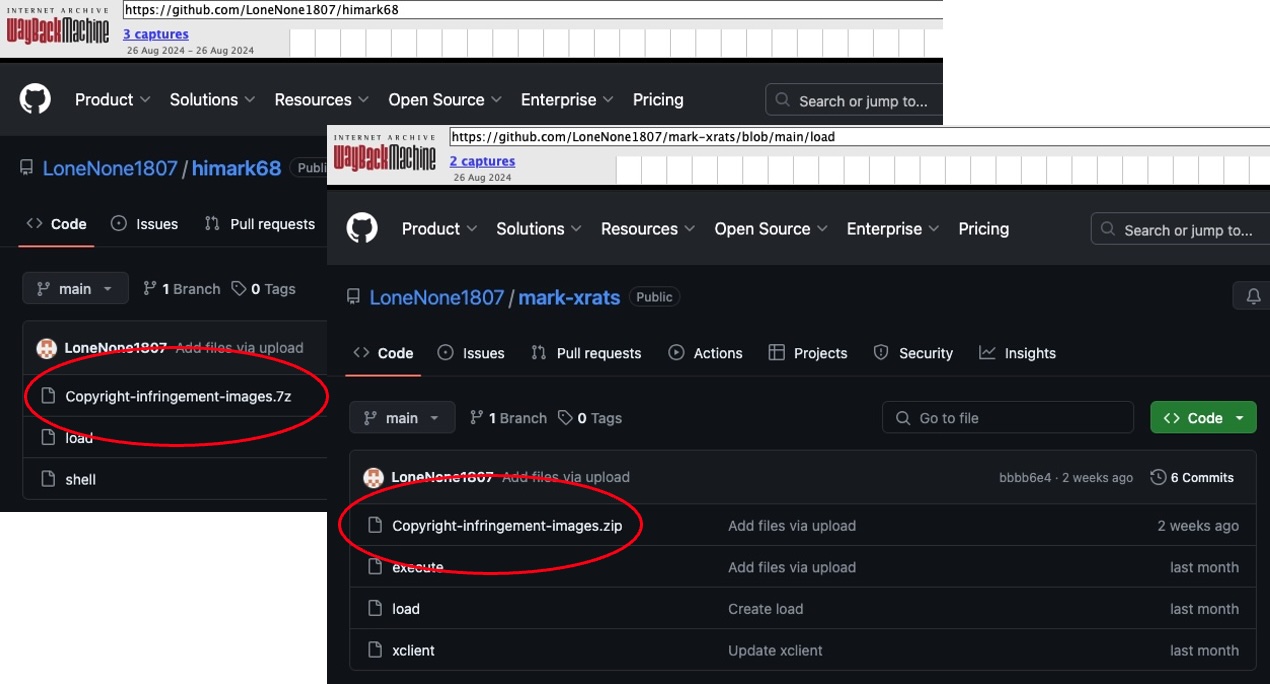

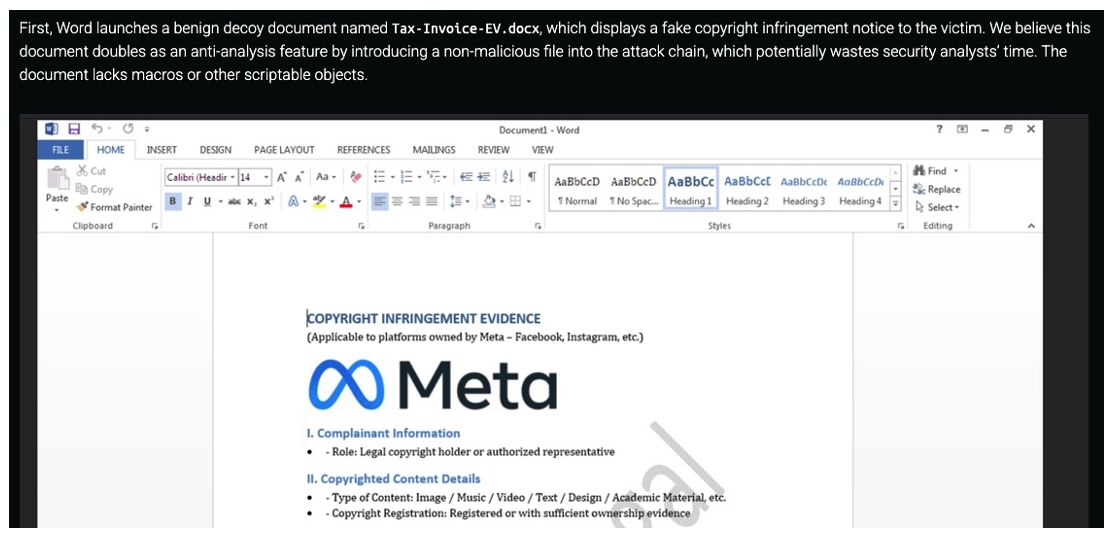

There’s another thing we noticed about LoneNone’s older RedAV/XWorm/Redline campaign from last year: some of the malware component repositories contained archives that appear to be spam lures:

Figure 11: Copyright Lures

This caught our eye because copyright infringement was the theme of the original spam lures sent to our client as outlined in our original blog post:

Figure 12: Different malware campaign, same lure

As we continued our investigation, one of our Beazley Security researchers decided to investigate the “uninteresting” accounts in the dataset. There are a handful of accounts that don’t (at first glance) seem to offer any operational capability to a malware campaign, like Netflix and PyPi. One of the other accounts that we originally passed over was for `dmca.com`. Not to be confused with the related, but separate entity that is the DMCA law, dmca.com is a private, commercial organization that provides a service to monitor and send DMCA takedown requests on behalf of customers.

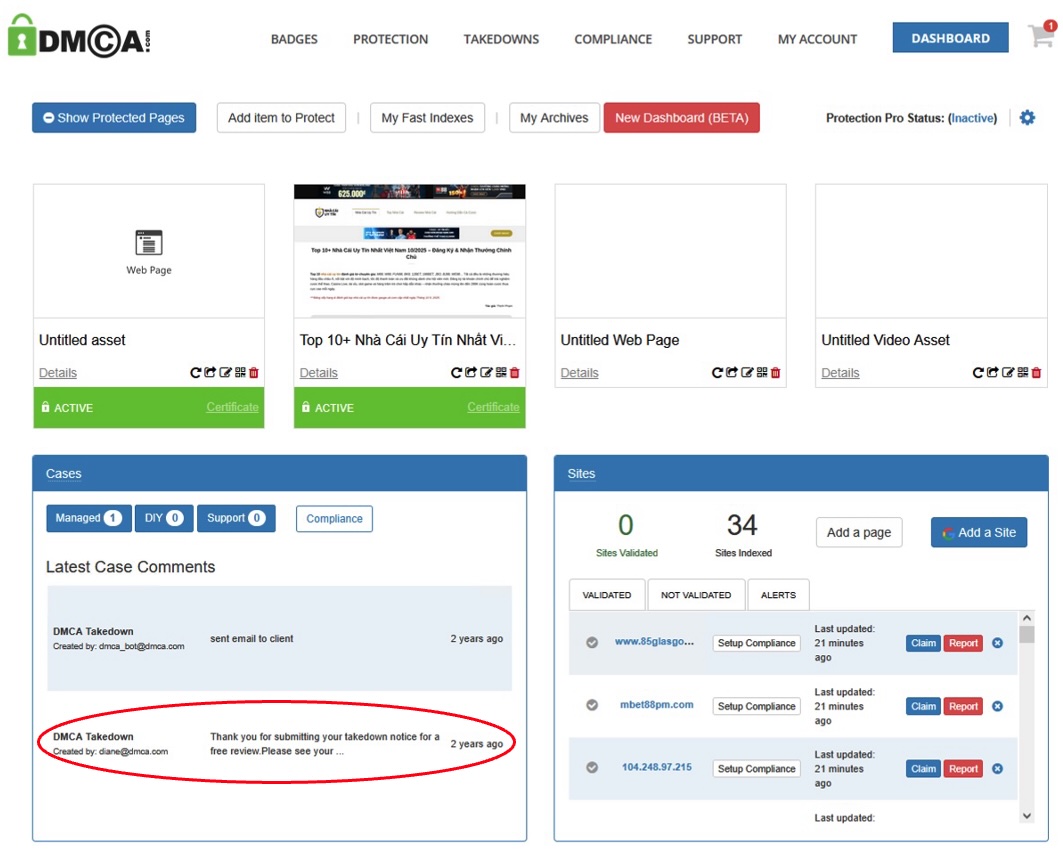

When we studied LoneNone’s DMCA account we found that they not only registered two Vietnamese language gambling related websites for copyright infringement monitoring and protection services:

Figure 13: Two VN gambling sites registered for protection

They had even submitted a takedown request of their own:

Figure 14: DMCA Takedown Request

We’re unsure what LoneNone’s interest is in protecting those gambling related sites, and we don’t know the context behind the filed takedown request, but we believe it’s safe to say this threat actor had some kind of affiliation with Vietnamese gambling sites and the takedown request was part of that relationship.

Aside from being an interesting sidenote in this person’s activities, we believe this is why LoneNone seems to favor copyright infringement themes for their spam campaigns: it’s simply something they are familiar with and can make convincing fake documents for.

Also, we are not the only research group that is tracking copyright lures from this exact threat actor; this has been observed and reported by phishing defense company Cofense as well, which you can read about in their blog here.

Hey look, I recognize those IoCs!

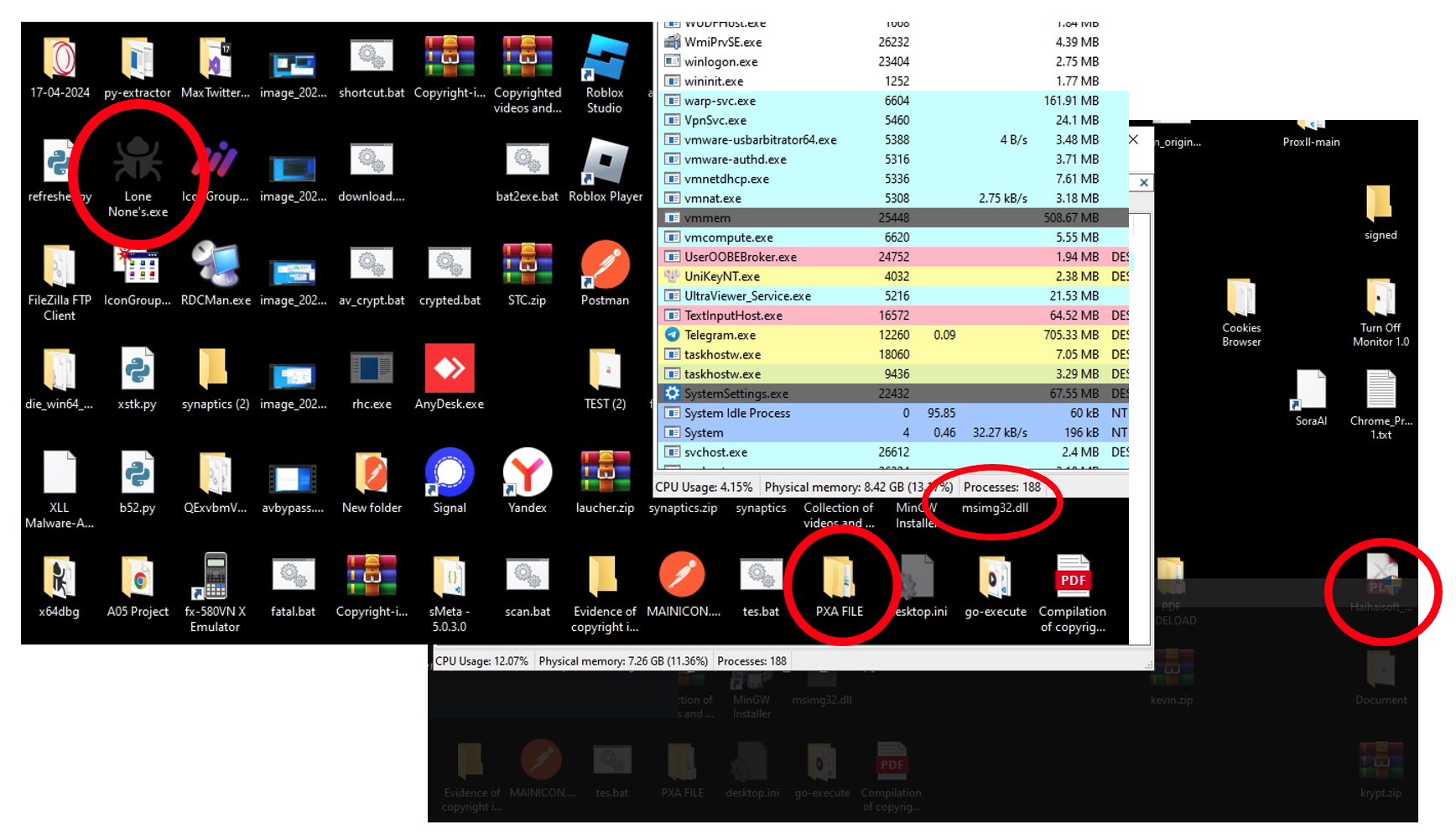

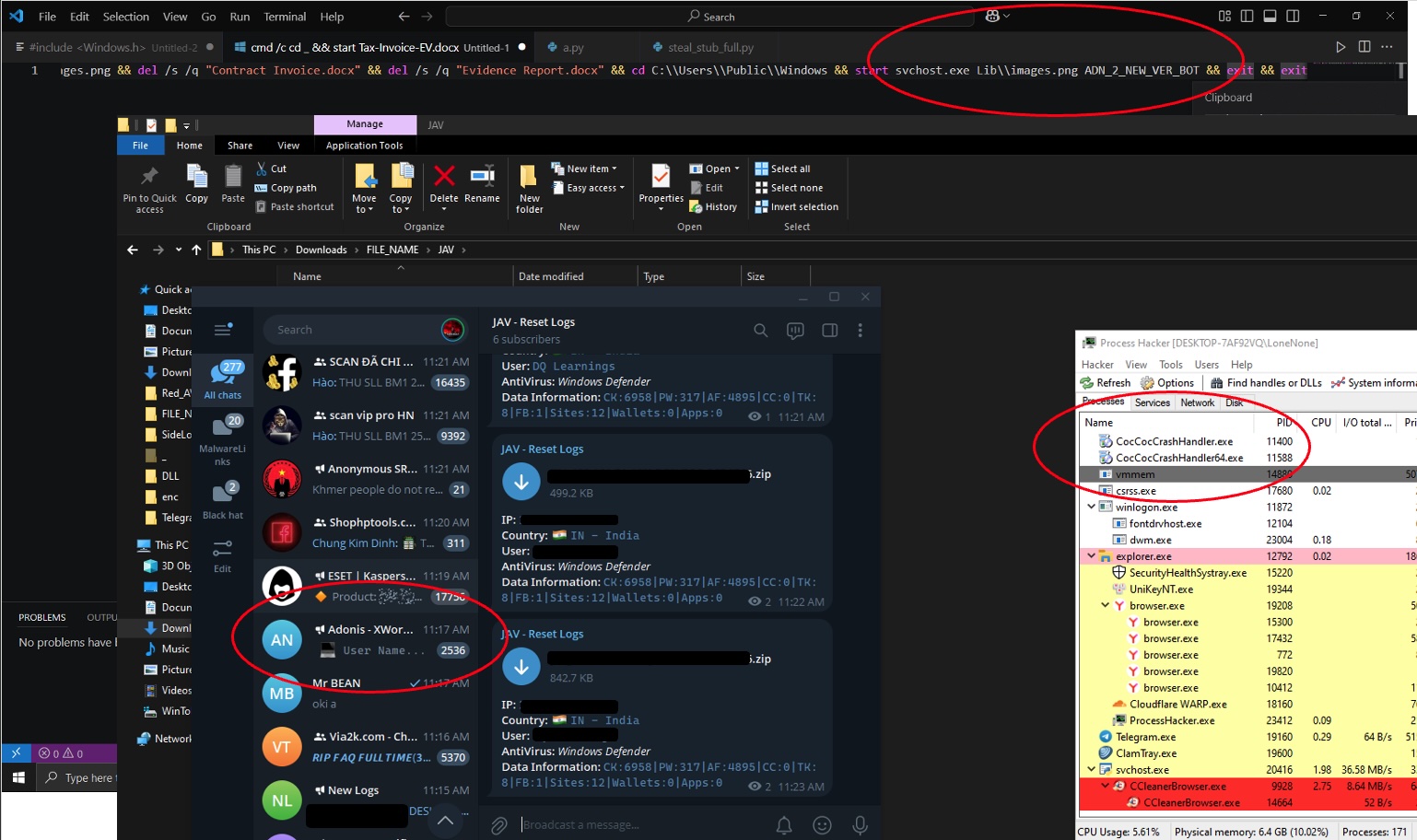

By far the most amusing uploaded objects we had access to though were desktop screenshots of LoneNone’s machine. Infostealers are commonly created with screenshot capabilities, for times when there may be an application containing valuable information that the malware maybe wasn’t programmed to scrape for data. In our case, the screenshot of the threat actor’s desktop revealed a whole load of interesting operational information we wouldn’t otherwise know:

Figure 15: Malware internal name (PXA), analysis tools, component objects, targeted software

The above screenshot shows a working folder confirming the internal name the author gave the malware (PXA), a supposed DLL that has a system name similar to the one used as a side load payload in our original MDR case (msimg32.dll), legitimate document software that coincides with a previously reported campaign from this threat actor (Haihai soft), and the malware author’s handle (LoneNone), found on a file with an icon indicating it is a binary debugger tool called x64dbg.

We also had screenshots showing:

Testing the deceptively named ‘images.png’ WinRAR app from our original article

Logged into a Telegram channel called ‘Adonis – XWorm’, which Beazley Security asseses to be related to last year’s campaign

A program (process hacker) monitoring the CocCoc browser, a Vietnamese language browser which was also mentioned in our original article

Figure 16: old Telegram, targeted browsers, new attack chain components

Malware Campaign Telemetry; Straight from the Source

Above all, the best (funniest) accounts we discovered were for the Kleenscan and Cloudflare services. Those accounts were directly used to test and deploy attack components used in the very campaign launched against our client. Kleenscan is, on the surface, a comprehensive file scanning service similar to what VirusTotal provides. However, they explicitly state on their site that they “do not distribute”, meaning they do not share scan results with the cyber security community or the antivirus vendors. This means their service is intended for malware authors to keep scanning and crypting their payloads until they are “Fully Undetected” (FUD). As such, you can find them advertising on cybercriminal forums such as Hackforums and BlackHatWorld.

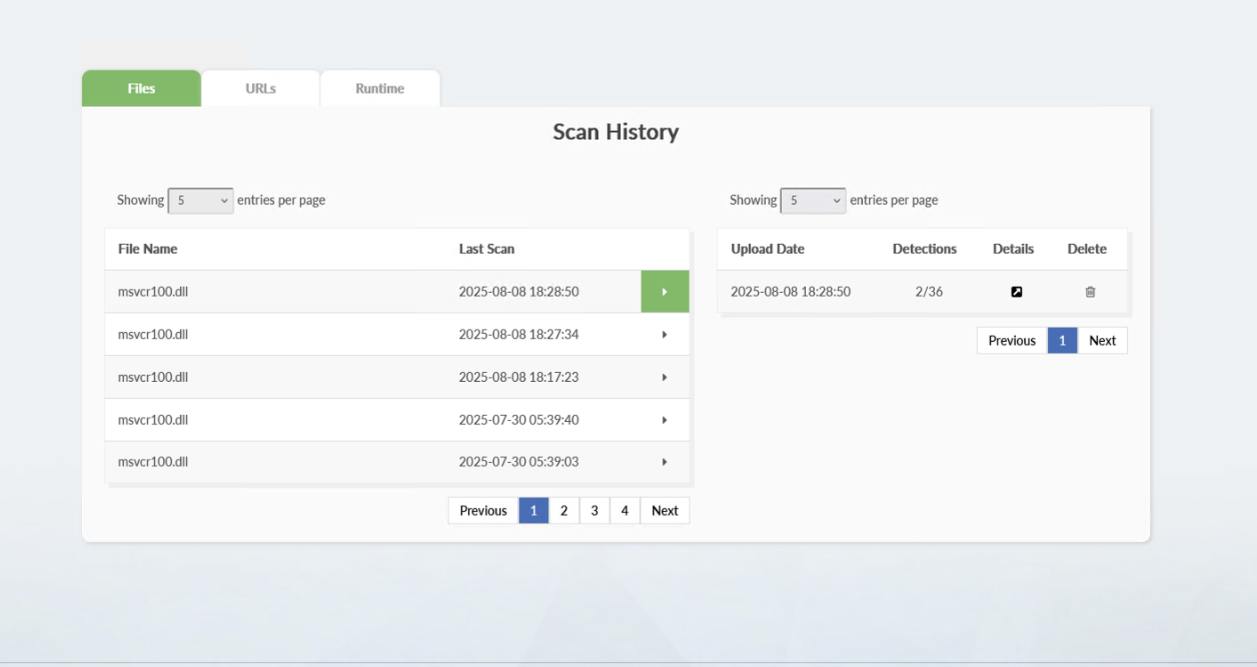

LoneNone has been using Kleenscan for a while, and we were able to identify scans of files that looked like they were from past campaigns, even older than last year’s RedAV/XWorm/Redline campaign. The best finding however, was the below scan showing them verifying the very same sideload payload that we later saw used against our client. LoneNone checked it repeatedly, right up until they launched their attack:

Figure 17: LoneNone testing payloads used against our client

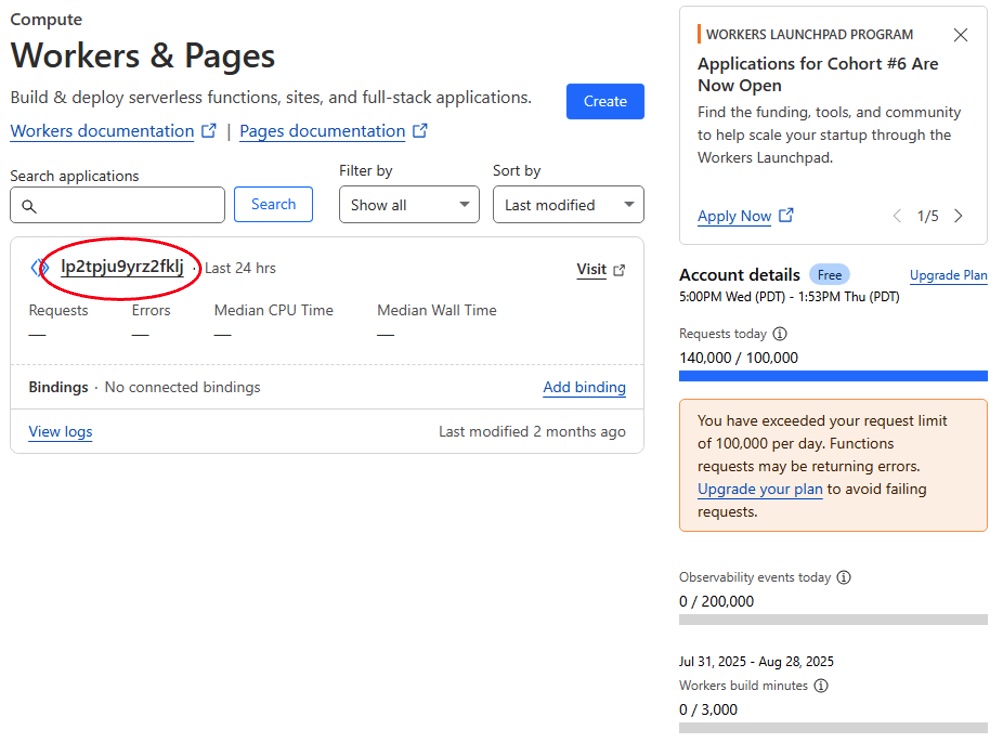

We also had reviewed the Cloudflare account used to deploy the worker instance used as a hop to hide the Telegram C2 endpoint. This domain was the same domain we saw as part of the attack campaign we unravaled in our first blog.

Figure 18: Cloudflare configuration page for the C2 redirector

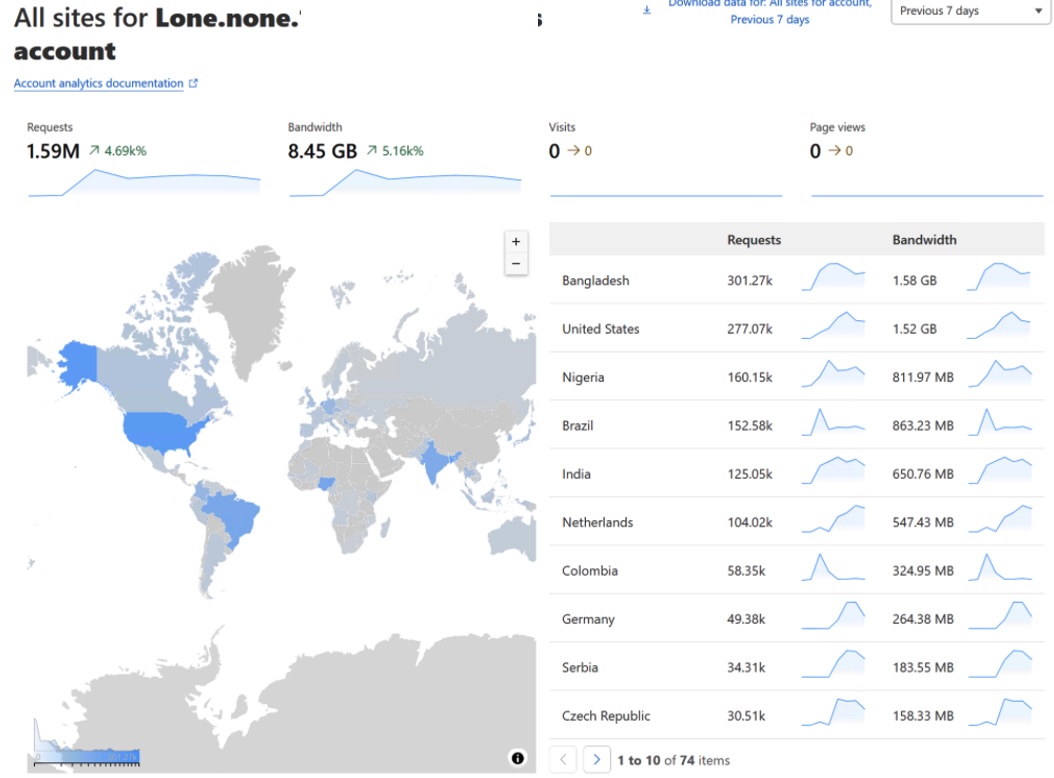

So naturally, we worked to get insight, telemetry, and traffic data for this malware campaign. Funnily enough, by the time we looked at this Cloudflare panel, the free rate limits imposed by Cloudflare had already already been reached. By then, the domain was publicly known so it’s likely bots and researchers were hammering the worker app. However, we were still able to get pretty telemetry graphs and maps, straight from the source!

Figure 19: Marketing friendly graphs and charts!

Conclusion

Most security analysts and responders that work have an understanding of the typical attack chain elements; after all, they’re the parts of a malware campaign that play out in our own and our clients’ environments. These are the components of the “attack chain” that we see on a daily basis.

Every now and then, however, we get opportunities to go “backstage” and peek behind the curtain at the preparation and monetization infrastructure that isn’t often seen. While they may not seem as relevant to the protection of client assets, this type of research can provide valuable insight to motivations and capabilities that we would otherwise not see.